So it started to get real once I was waiting for my connecting flight in Denver, Colorado to Bismarck, North Dakota and I flicked through my Feedly stream. "War Crimes On The Northern Plains" "More than 140 NoDAPL Water Protectors Arrested Overnight" "Police Brutality at Standing Rock Soars With Use of Out of State Law Enforcement" "Brutalized by Police and Jailed in Dog Kennels."

Then I checked the email from my producer at AJ+. "Safety is first – please not get close to anything that could put you in danger." "The police will be removing people from the camp." "It is an honor to be there and cover this story and be part of history."

Oh yeah, this one was much more than just a trip. This one was something much much more than that.

I've been following this story for months, it struck a chord for many reasons, and ever since it was on my radar, I have been aching for a way to get out there or be involved, so when an opportunity to cover it for AJ+ in 360 video came my way, I was on it. I was originally planning to leave sometime late the week of October 31, but the events of October 27, the ones that spurred those headlines above, made it a much more pressing story, so first contact with AJ+ to the time of my flight went from 10 days to just under 48 hours. I was on a plane before all the details were even finalized.

It was go time.

If you're not familiar with what's been happening in North Dakota, I VERY highly encourage you to research the story on your own. Just Google “Dakota Access” or “NoDAPL” or “Standing Rock” and there will be no shortage of information.

In a nutshell, a pipeline that is set to carry oil from the Bakken oil fields of North Dakota through 4 states to Illinois is meeting resistance at a crucial juncture where it is set to cross the Missouri River. The pipeline was originally routed to cross the Missouri River about 35 miles north near Bismarck, the capital of North Dakota, but, and this part is crucial to note, residents feared it could threaten their water, so it got re-routed here…in Cannonball, North Dakota, less than a half mile upstream from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, where it immediately threatens not only the water supply of the Lakota Indians on this reservation, but also up to 17 million American residents downstream.

Additionally, the route of the pipeline has already destroyed sacred sites and burial grounds, and is currently routed to destroy even more.

On the night of October 27th, under the instruction of Morton County Sheriff Kyle L. Kirchmeier, and with the backing of North Dakota’s Governor Jack Dalrymple, over 140 protectors, including elders who were praying for the sacred grounds, were met with violent response from authorities that included Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) private security, the National Guard, as well as officers from North Dakota and 3 other states. Protectors were pepper sprayed, shot with rubber bullets, and many were marked on their wrists with numbers and thrown into 12’ x 8’ dog kennels with up to 15 others. I spoke with several medics who were treated this way while treating injured protectors, and they weren’t released until 3 days later. While I was there, Amnesty International showed up and the U.N. sent a team to investigate human rights abuses.

It is important to also note that the Lakota of the Sioux Reservation still view all of this land as their own under a treaty from 1851. Parts have since been wrangled from them under controversial ‘imminent domain’ claims, unrecognized by the tribe, and have been sold to private, non-tribal buyers, who have in turn sold swaths to the developers of the Dakota Access pipeline. If it reads like a highly organized gangster scheme, that’s because it basically is.

Anyhow, this was a story that brought everything that I care about together into one tight package - racism, environment, immigration, big business, national security, the economy, equality, human rights. You name it, this story was ALL of that. And now, finally, was my turn to experience this firsthand.

As I began my drive the next morning from Bismarck to Cannon Ball, a 45 mile straight-shot down the 1086, I wasn’t even 10 miles in before I ran into a roadblock, blocking the freeway to keep it clear for those constructing the pipeline, meanwhile re-routing me on a 20 mile detour that took me inland and then back around. When I made my approach into Cannon Ball an hour later, the signs began to make themselves more evident, beginning with a police checkpoint at the juncture of the 24 and the 1086 freeways, just about a mile south of the original camp, Sacred Stone, and 7 miles south of the Oceti Sakowin Camp, the largest of the camps and the one closest to the pipeline.

Oceti Sakowin was my destination.

As I made my way around the final ridgeline, the camp came into view in dramatic fashion - what looked like hundreds of tipis and tents and flags of all shapes and colors were stretched across an open prairie and the blue sparkle of the Cannonball river marked the horizon. It was actually quite beautiful.

I reached the end of the road, which in this case was a bunch of cones prohibiting us from going any further, and the entrance to the camp just of the side of the road. I checked in with the media tent, filled out the recommended form in the legal tent so they’d have my information in case of any arrest, and started walking around the grounds to get better acquainted with Oceti Sakowin.

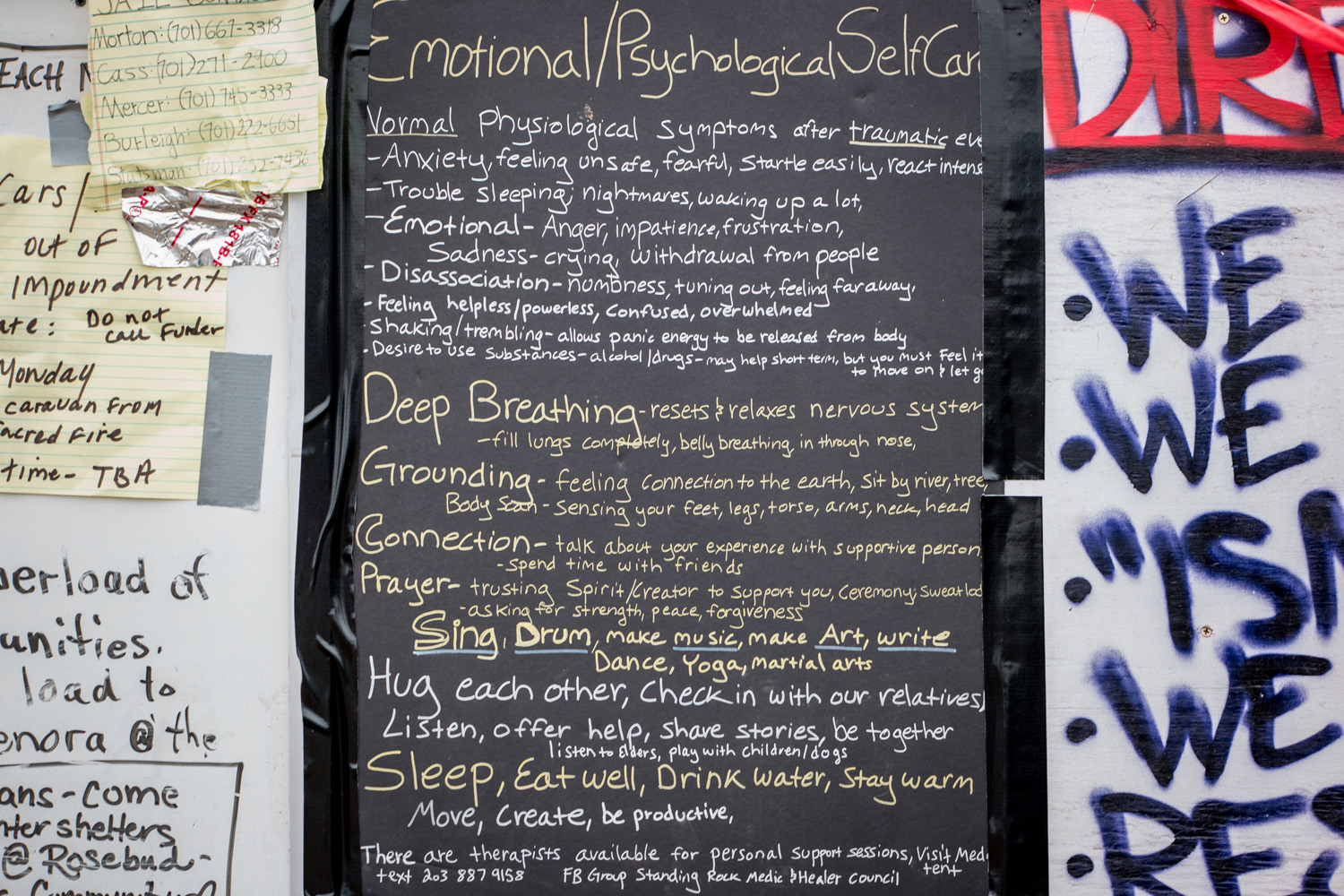

I don’t know why, but I was surprised by what I found, even though it was exactly what I was hoping and expecting to find - prayer circles, communal fires, elders sitting around the spirit fire puffing on their ceremonial peace pipes while simultaneously discussing the situation and guiding the youth of their tribes. Wellness and healing tents. Communal meals.

The state of affairs of where our country's interests truly lie can be summarized by the most telling emotion I had that day - I felt safer and more at peace as soon as I got off of the jurisdiction of my own country and onto Standing Rock Sioux Reservation territory. From the guns, tasers, tanks, batons and riot gear to the peace pipes, sage, horses, prayer circles and feathers - it was clear only one side, and which side, truly had our best interests as a people in mind.

And the organization of the camp was intensely striking. I mean, they had everything, more was coming in, and all basic services and infrastructure was created out of thin air and pure will with the help of super committed and passionate beings from all walks of life. I spoke with doctors from New Zealand, lawyers from Boston, massage therapists from California.

And the flags.

It’s hard not to be awestricken by the flags.

There were over 200 flags that lined the main road through camp, each of which represented a tribe or organization that has descended upon this remote area to show their solidarity with Standing Rock. Some of these tribes haven’t spoken or communicated in over a decade. And they’ve come together for this. For example, the Crow Nation hasn’t been welcome in Sioux territory since the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. Just this past August, representatives from Crow Nation brought peace pipes and hundreds of pounds of buffalo meat as a peace and solidarity offering.

At the end of the road of flags lie the medic tent. It was here that I was to meet one of my point of contacts for this story, Noah, and it was here that I quickly heard some firsthand accounts of what had happened a few nights before, for as I arrived, a group of volunteer medics, including Noah himself, that had been beaten, arrested, marked on their wrists with numbers, and thrown into 12x8 dog kennels for 3 days while attending to injured water protectors were released and giving their testimonials for the medical department’s records. You can see parts of that interview I conducted with them in 360 video at AJ+.

The next day, I had just finished an interview with Linda Black Elk, the liaison between the herbalists and the campers, and Dr. Sara Jumping Eagle, a physician on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, outside of their der (pronounced like bear...apparently the real name for a yurt), when a truck came by. The driver saw my media badge and instructed me to head towards the ridge - something was happening. We looked up towards it and there was a line of police officers and DAPL security all outfitted in full riot gear with rifles all pointed in the camp’s direction. Behind them was a visible piece of the pipeline being moved while tractors prepared its path on the other side. So I jumped in a van with Dr. Sara Jumping Eagle who took me towards the action. We stopped in a thicket of brush to watch from afar for a little while, and started noticing a group from the camp start to make their way up the ridge towards the officers.

They were face to face.

Things were tense.

As I was standing there shooting some footage, a pickup full of water protectors came by and asked me to hop in the back, so without thinking (in retrospect probably not the best practice to get into), I did. I jumped into the bed of the truck and headed towards the action. I jumped out when I started to feel I was getting a bit too close for comfort. I set up my rig and tried to figure out what was going on. Horses with whooping indigenous Native Americans came flying by me, drum lines came passing by, and prayer began on the riverbank below the officers on the ridge. There was obviously an agenda on both sides, but it was unclear what that was. Several rumors began to circulate. One was that some water protectors were crossing the river to test the waters and see if they can get to the construction site to block the pipeline. Another was that the DAPL side was using that as a diversion while they proceeded with construction on an unseen portion of the ridge.

I still don’t know.

But I do know things were definitely coming to some sort of head.

Meanwhile, helicopters, private planes, and drones with facial recognition were allegedly violating no-fly zones to keep a watchful eye on the 'savages.'

As I mentioned before, and worth repeating here, it is important to remember that the original permits for this thing apparently had the pipeline routed to cross the Missouri River 35 miles upstream near Bismarck, the capital of North Dakota, but they denied it because…not so ironically…they were worried that it might contaminate their water!

So they decided to move it downstream.

Here.

Less than a half mile from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation and the main source of water for the tribe and all citizens downstream.

And here we are.

Anyhow, the crowds dispersed and regrouped in various parts of the camp.

Soon after, while I was offloading and decompressing back at camp, I heard some hoopla near the spirit fire, a communal gathering place in the center of camp, a base for announcements, ideas, prayer and ceremony. While the action was happening, a member of the UN was at camp, and this was a bit of a debriefing of what was said and is being done.

After the briefing I got a chance to speak with Roberto Borrero of the Indian International Treaty Council, human rights observer accompanying Grand Chief Edward John of the U.N., about his role in the report that will be presented to the U.N. regarding human rights violations as well as the issue of criminalizing the water protectors, and the man that was standing right next to him, who happened to be Doug Good Feather, the Executive Director of the Lakota Way Healing Center and…get this…grandson to Sitting Bull.

The Grandson to Sitting Bull.

When he looked at me and said “My Grandpa Sitting Bull said…let’s put our minds and our hearts together, to see what kind of life we can make for our children,” I got goosebumps all over my body.

It was impossible not to feel completely humbled and lucky to be here at this very moment - a pivotal and historical moment in the history of the Native Americans and America as whole.

The next morning, it almost seemed like a a calm before the storm. As I walked around camp with my friend, and incredible photographer (who was there shooting on a Hasselblad), Chantal Anderson, the quiet but undeniable murmur of people getting ready for something was thick in the air.

And they were, soon we’d learn, for more than one reason.

The first being the proximity of the cold winter months. They were just around the corner, and as the tribes and water protectors have vowed to remain at camp through those months, there were some preparations that needed to be made. Permits for permanent structures were being acquired, permanent tipis and ders were being constructed all around us, truckloads of wood were being brought in and chopped up for warmth and cooking, and the kitchens were preparing for storage and allocations.

This was also the scene of one of the most unforgettable moments of my life…an interaction with a tribal member that left me literally speechless. After I had finished interviewing the kitchen staff on how they’re preparing for the winter months, and how they’re keeping a camp this size properly satiated, I felt a tap on the back of my knee. I turned around came face to face with an elderly Native American man who was using a rod to prod at the camera hanging on my side. I asked him “can I help you?” He immediately shot back “Can I help YOU?” I said something to the effect of “I’m not sure. What do you need.” He replied with “What do YOU need?”

That’s when I realized I just fell into a confrontation. It went back and forth like this for well over 5 minutes, him asking me what I wanted and why I was there. Him asking me if I was getting paid and if I was exploiting what was happening at the camp for a paycheck. Him stating to me that when I was done with my job that I’d get to go back to my comfortable home. He was playing the role of devil’s advocate to every response I had. I was starting to get frustrated and told him as much. “This is starting to get very irritating.” He looked at me and told me “Tell me about it!” I reminded him that he started this. He responded, “No YOU started this.” When I told him I was simply there as a journalist to help get their story out to the world, and I was trying to bring the fundamentals of their cause to the public eye, he responded, “My cause? What’s my cause? You didn’t ask me anything.” I responded, “Well, water! And your rights. I assumed since you were here,” and he cut me off…”Ohhhh…you assumed!”

Finally I just looked at him and said, “What’s it going to take to end this conversation?” He paused. He smiled. He looked me in the eye. He extended his arm. He said “A handshake.”

The tension immediately broke. When I shook his hand, he held onto it. “What you just experienced is just a tiny bit of what we’ve been experiencing for 500 years,” he told me. “But now I know you’re with us. Thank you for doing what you’re doing.”

I was humbled. I was speechless. I was empathetic, I was sympathetic and I felt like I had just been blessed. This proved to be a very powerful moment for me. And as I’d deduce later, this was very probably a result of certain parts on the administrative side tightening up their operations, including, but not limited to, media access and vetting, as there have been several reports of DAPL plants posing as media to infiltrate the camps.

Anyhow, the second reason the air felt ripe with calculated preparation was what happened the following morning, Wednesday, November 2.

Imagine this…your uncles, aunts, grandparents, cousins, parents, brothers and sisters are buried on your property. The U.S. government sells that piece of your property to someone that isn’t related to you at all, despite a long standing treaty that you have the rights to the land. An oil company comes in with tanks, an army of armed police, a fleet of bulldozers and digs up and desecrates all the remains of those relatives and ancestors.

Well, that’s precisely what’s happening to all the people here.

You see, on that very same ridge that I was whisked off to the day before, lies a tree. Before that ridge lies a river. That tree, on the ridge, on the other side of the river, marks a sacred burial site that the tractors were getting dangerously close to - Turtle Mountain. A group of water protectors and elders used makeshift bridges to get to that side of the river, still on public Army Corps of Engineering land, for ceremony and prayer over the sacred site. They were met with a military style line of police and security, who were clearly off of their jurisdiction, armed with rifles, pepper spray, and an unknown white substance, who destroyed the bridges while the protectors were on them. A line of water protectors praying while standing waist deep in the water with their arms in the air were attacked with mace, and Erin Schrode, a journalist who was there with “Gasland” director Josh Fox, caught the very moment on video that she was shot in the back by a rubber bullet.

This made clear what was happening the day before. It’s fair to assume that the water protectors were doing recon to see how close the construction was to the sacred site.

Their ancestor’s sites were about to be desecrated.

They were concerned.

They wanted to pray.

This is a story that has not ended, and, if we’re lucky, it may never have an ending, as it simply marks another pivotal point in the evolution of the human mind and the resilience of our communal spirit. It is important to remember that, if this had happened 10 years ago, more likely than not, no one would have ever known about it. As a matter of fact, it’s been happening for well over 500 years to the indigenous peoples of this land, and not until now has the mass population had the tools to effectively battle it and bring the injustices to scalable attention.

These police officers, this governor, these oil companies…they couldn’t have imagined that something like this would have taken such a strong root in the public eye. They’ve grown so used to doing what they’ve been doing and getting away with it, far from meaningful scrutiny. You can see in how the have handled the situation, as well as the statements they’ve been giving to the mainstream media - it’s the same tired lines and methods they’ve been feeding the public for decades and centuries.

But what they fail to recognize, and this may serve as a big lesson, is that things have changed.

This is the first time in human history that we've had the tools and the collective voice that we do, free and clear of the restraints of bureaucracy, and the more we learn how to best use those tools, the more we'll begin to realize how connected we really are.

I don't see the end of anything, I see the beginning of everything.

And they’re feeling that heat.

As a matter of fact, just this week, 2 police officers have handed in their badges in support of the water protectors, major editorial boards including the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times have thrown their support behind the protectors, President Obama said that the Army Corps of Engineers is looking into ways to re-route the pipeline, Norway’s biggest bank, a major financier of the pipeline has announced they may pull their over 400 million dollars in backing, The Army Corps of Engineers may delay the permitting by up to 60 days, effectively shutting down the project as a whole, a group of over 500 clergy members from various denominations showed up to pray and support, a water protector rushed to the front line to offer candy and sweets to the police, a moment that was caught on film by the very journalist that was shot in the back the day before, and as I type this, a March for Forgiveness to the Morton County Police Station is being organized by the tribes, literally to forgive the very people that just hours before were firing bullets and tear gas at them while protecting a corporation that was desecrating their sacred sites.

This has turned into a global phenomenon.

And we are the sole reason for that.

Which is why perhaps the most frustrating aspect of this entire thing has been how silent our two main ‘presidential’ candidates had been on not only the topic of DAPL, but also of climate change as a whole. Save for a short non-committal form letter paragraph released by the Clinton campaign, it’s as if this modern day cowboys and Indians scene wasn’t even happening. And that’s a distressing symbol and reason that we need to keep the pressure on, no matter the outcome.

This is not a Native American story or an oil story or a rural story or a far away story.

This is your story. My story. Our story.

This is the story of life.

Very literally.

For if water, the source of life, is not sacred...then nothing is.

And I firmly believe that if you can't see that, then, well...that's the ultimate sign that you’re due for a break from your comfort zone.

You will be challenged.

You will be frightened.

You will be confused.

You might cry.

You will laugh.

I did all of those things last week.

But those are all the very things that will remind you that you are alive.

Those are the very things that remind us that we are all connected.

Those are the very things that provide us with the perspective we need to remain on the right side of history, the right side of evolution.

It’s near impossible to walk away from an experience like that without a positive view on people and the future of humanity. You don’t see this testament to the resilience and good of the human spirit by watching it on a backlit screen, you get it by being with the people. For when you’re there, when you’re actually part of it, you transcend the profit-driven sensationalism, and can’t help but realize what a remarkable testament to the human spirit the power of being present and connected to community truly is.

After this experience I'm convinced that community is not a noun, but rather an emotion. A necessary one we have so strayed from in modern westernized culture as we have focused on isolating ourselves in our own echo chambers, we have forgotten how to be human. Anger, depression, confusion, restlessness, frustration…all modern signs of disconnect. But the more connected we become, the more connected we realize we all are, and the more important community becomes again.

We may have strayed, but events like this sure do make it seem like we're making our way back home.

So if you don’t care, goddamnit start caring. Because if you don’t care about water, then you LITERALLY don’t care about life.

It really is as simple as that.

As these thoughts were racing through my head, it was time for me to bid farewell.

At least for now.

So as I stood in the communal dining tent and grabbed a piece of freshly cured jerky made from the bison that one of the tribes brought as an offering just a few days before, I began plotting how and when I was going to return. A quote kept prodding at the back of my head.

“Now I know you’re with us.”

There’s no doubt about that.

“Mni Wiconi” (Google it)